We’ve discussed in previous postings the impacts of early adversity on health and brain development (Great Vine Blog: Parenting Kids Who Are Ready to Parent, 2015). We’ve also talked about the impact of early adversity on our food preferences (Great Vine Blog – Food for Thought: Connecting the Dots Between ACEs and Food Preferences, 2016). Today we’d like to take a look at how these two factors can potentially come together to create the “Perfect Storm Effect” on a particularly important part of brain function, that of memory.

Research has clearly indicated that early life stress, or adverse childhood experience, has a detrimental effect on both cognition (Chen & Baram, 2015) and health that can last long into adulthood (Westfall & Nemeroff, 2015). There is also increasing evidence that eating a diet high in fat and sugar can also have a lasting impact on cognition (Belharz, Maniam, & Morris, 2015).

Recently a group of researchers has begun to explore the idea that when adversity and poor diet are combined, they might serve to magnify one another in their impact on the hippocampus, a brain structure that is important for memory (Morris, Le, & Maniam, 2016). It isn’t hard to imagine these two factors coming together. We often see families that are struggling with a variety of adversities relying on foods that are convenient and inexpensive, which often means they are high in sugar, salt, and fat.

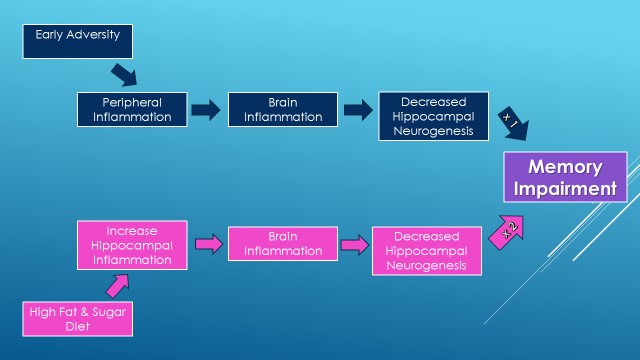

Why is it that these two factors in particular are important? It seems to be about inflammation. Specifically, in regard to early stressors, what we know is that this leads to an inflammatory response in the body. Inflammation in the body leads to inflammation in the brain. When the brain is in a state of inflammation, fewer of the new neurons that are being born in the hippocampus make it to maturity. This lack of new neurons in the hippocampus leads to memory impairment (see figure 1). Similarly, in regard to poor diet, consumption of foods high in fat and sugar cause an increase of inflammation in the brain, specifically the hippocampus, which in turn leads to memory impairment (Belharz, Maniam, & Morris, 2015). In theory, at least, the damage coming from two paths would multiply its impact, since both factors have been shown to affect the growth of new neurons in the hippocampus (see figure 1).

|

||

It seems critical, not only for us to understand this potential combined effect, but also to support parents in understanding the importance of making choices that will reduce the stressors their children are exposed to and result in feeding their children healthy foods. . By so doing, they will be protecting their child’s developing brain and optimizing their development. The Growing Great Kids curriculum provides many conversation guides designed to facilitate these kinds of discussions. Check out the following sections specifically:

Growing Great Families: Unit 2-Reducing Stress: Tools for Stress Management

o Protecting Your Children from Toxic Stress

o Sizing Up Your Strengths…Reducing Stress

o Warning Signs for Stress Overload

o Problem Talk…A Problem Solving Skill

o Growing Your Support Network

Growing Great Families: Unit 4-Blueprints for Emergent Use

o #3 Reconnecting Parents to their Child’s Needs During Times of Stress

GGK – Prenatal Manual

o Unit 1 – Module 4: Text Messaging Your Baby

o Unit 2 – Module 5: Parenting to Grow a Resilient Child

o Unit 3 – Module 3: Healthy Pregnancy Healthy Baby

o Unit 4 – Module 2: Power Down Stress…Power Up Happiness

GGK Birth-12 Months Manual

o 4-6 months Unit – Basic Care Module

o 7-9 months Unit – Basic Care Module

GGK 13-24 Month Manual

o 13-15 months Unit – Basic Care Module

o 22-24 months Unit – Basic Care Module

GGK 25-36 Month Manual

o 31-36 months Unit – Basic Care Module

Preschool Manual

o Module 3: Childhood Nutrition

Most parents are unaware of the connections between stress, the foods they feed their children and brain development. Sharing what you now know with parents can be a great motivator for parents making positive choices even when a family’s resources are limited.

Works Cited

Belharz, J., Maniam, J., & Morris, M. (2015). Diet-induced cognitive deficits: the role of fat and sugar, potential mechanisms and nutritional interventions. Nutrients, 6719-6738.

Chen, Y., & Baram, T. (2015). Toward understanding how early-life stress reprograms cognitive and emotional brain networks. Neuropsychopharmacology.

Great Vine Blog – Food for Thought: Connecting the Dots Between ACEs and Food Preferences. (2016, January 26). Retrieved from Greatkidsinc.org: https://www.greatkidsinc.org/blog/food-for-thought-connecting-the-dots-between-aces-and-food-preferences/

Great Vine Blog: Parenting Kids Who Are Ready to Parent. (2015, December 8). Retrieved from Greatkidsinc.org: https://www.greatkidsinc.org/blog/parenting-kids-who-are-ready-to-parent/

Jacka, F. N., Cherbuin, N., Anstey, K. J., Sachdev, P., & Butterworth, P. (2015). Western diet associated wtih smaller hippocampus: A longitudinal Investigation. BioMed Central.

Morris, M. J., Le, V., & Maniam, J. (2016). The impact of poor diet and early life stress on memory status. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences.

Westfall, N., & Nemeroff, C. (2015). The preeminence of early life trauma as a risk factor for worsened long-term health outcomes in women. Current Psychiatry Reports, 90.